William Branigin, a young journalist for The Washington Post, was roaming around in the villages of Sonargaon in Narayanganj in the first week of June 1981. Soon, he realised, the village was weeping. Even one week after President Ziaur Rahman’s death, a sense of despair prevailed in every corner of the village. He penned down his experience in a village in Bangladesh and got it published on June 8. It was titled: ‘Bangladeshi Villagers Despair at Loss of President’.

President Ziaur Rahman’s death was a bolt from the blue. Just three months before his death, on March 28, Stuart Auerbach of The Washington Post termed him Bangladesh’s number 1 motivator for his role in motivating the people to solve the country’s food problem. A country that suffered from a deadly famine in 1974 that cost around a million lives, was producing more crops than ever and was aiming for self-sufficiency in food.

Poet, scholar and most importantly the agriculture secretary of the government, AZM Obaidullah Khan, as quoted by Auerbach of The Post, gave the credit to Zia, for all the good reasons. In post-independent Bangladesh, when the country was a socialist economy, the agricultural development authority used to distribute fertilizers through a limited number of dealers who had licenses and permits. Prominent political scientist Rounaq Jahan, who authored the book Bangladesh Politics: Problems and Issues in 1980, wrote how in those days these permits and licenses were used as a tool for political patronage and were mostly distributed to the ruling party supporters and sympathizers who sold and resold them to others causing inflation.

One of the first few measures of the new government under Zia was to rely on the market for the distribution of agricultural products and technologies. Mahabub Hossain, a senior research fellow at the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, in his research, has shown how technology contributed to the growth of crop output in the post-1975 period.

This was echoed in the voice of Iman Ali Sarder, a 67-year-old farmer who was talking to William Branigin. “We were almost starving, but these projects have opened the villagers’ eyes. Now they don’t move to the towns; they stay and cultivate the crops,” he said. Iman Ali Sarder also claimed that the villagers could not sleep and eat for two days after hearing the news of President Zia’s death.

Another villager, 85-year-old Shajad Ali, who was sitting in a market stall, said, “We were known as the sick man of the world, but because of Zia our prestige has gone up.”

Statements from global and national leaders after his death are proof of this statement.

U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim in a message issued after his death called him ‘an outstanding statesman’ while U.S. President Ronald Reagan remembered President Zia’s ‘profound and compassionate commitment to a better life for his people and his dedication to the rule of law’. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi visited the Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi to sign the condolence book and issued a message saying, ‘President Ziaur Rahman led his country with distinction, giving special attention to the problems of development.’

The grief of the sudden death of President Zia was all over the Islamic world. King Khalid bin Abdulaziz Al Saud of Saudi Arabia sent a cable immediately on the night on May 31 after learning the news expressing his grief and the Royal Court issues a statement. President Anwar Sadat of Egypt declared three-day of state mourning in Egypt. The Organization for Islamic Cooperation adopted a resolution claiming that the OIC ‘considers His Excellency President Ziaur Rahman as an outstanding Islamic personality who during his lifetime had dedicated his entire energy to the upliftment of the people of Bangladesh by providing them a sense of direction and unity of purpose, and to further strengthening of Islamic solidarity.’

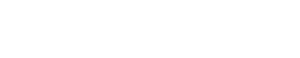

Suranjit Sengupta, an opposition leader in the parliament, lauded the dynamic leadership of President Ziaur Rahman in his speech in the parliament. He said, ‘The gathering of hundreds of thousands of people at his funeral proves how popular he was as a President.”

Indeed, he was.

On June 2, hundreds of thousands of people came to pay their homage at his funeral. President Zia’s funeral is the largest funeral in the history of Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Observer report read, ‘Nothing like it had been seen before […] the assemblage of lakhs of people at the Namaz-e-Janaja was a clear demonstration of their endorsement to the policy pursued by the late President.’

President Zia’s burial made it to the front page of The Washington Post on June 3 with the news “Vast crowd mourn at the burial of Zia.” A bird’s eye view photograph capturing the large crowd was published and the news read, ‘Hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshis poured through the streets of this crowded, dirt-poor capital today in a funeral procession for slain President Ziaur Rahman’.

Time, the famous American news magazine, explained why he was so popular. In its report “Bangladesh: Death at Night,” published on June 8, the magazine claimed ‘The slain Zia had been one of South Asia’s most promising leaders, a man who lived modestly while others chose corruption, who searched tirelessly for solutions to his country’s awesome poverty’.

But the most intriguing analysis of President Zia’s reign was published in The New York Times. In its June 7 report “Everyone Loses In Bangladesh Coup Attempt” the widely circulated American daily wrote: ‘If there are worse places than Bangladesh these days, much credit goes to Ziaur Rahman. From his rise to power in 1975 until his assassination last weekend, General Zia instilled new motivation in the New England-sized nation of 92 million people to produce more food and fewer children’.

In a follow-up editorial on June 12, the newspaper made an interesting comparison between Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s rule and the tenure of Ziaur Rahman. The editorial read: ‘Born out of a fracturing of Pakistan only a decade ago, Bangladesh early on gained a reputation as an international “basket case,” a metaphor for misery and hopelessness.’ Hoping that the institutional strength built over the years might outlive Zia it added, ‘President Zia’s unheralded achievements contain a lesson of sorts: No third-world country should be glibly written off. No society wants to be a basket case’.

Bangladesh, as the editorial claimed, thanks to the achievements of President Zia, was no more a country that can be written off as a basket case.